The Buc-ee’s Solution to the Housing Crisis

This was a submission to the Boyd Institute’s Housing Essay Contest that closed on 10/31/25.

Whilst traveling long miles across the vastness of America, the motorist, in wanderlust, may notice the inching of his metre to the left and empty. As such, the seasoned carsman will look over at those big rounded placards—billboards as they are—and spot for gaseous symbols in relation to an upcoming exit. In worry at his final notch, he might then notice an excruciating pattern regarding those exits: some passed have more gas stations than sense and others ahead, more dreadfully, have none at all. The driver might then glimpse a key piece of economics, that being of, Hotelling’s Law of Minimum Differentiation.

Harold Hotelling was the doctoral student of Veblen, Oswald V., Lover of England and her tea. Of his own students, he had been a doctoral advisor to the prolific neoclassical economist, Kenneth Arrow, and a statistics teacher to the small ‘l’ libertarian, Milton Friedman. Hotelling operated as a Georgist associated with the Paretian revival and a statistical patriot, one of the many university experts who loaned their services to the United States military during WWuntil2. Outside his study of minimum differentiation, he is credited as an inventor of principal component analysis, a key mathematical technique used to identify the core dimensions of variance in a dataset.

Hotelling’s Law of Minimum Differentiation, as established in his 1929 paper, “Stability in Competition”, posits the model of a linear city, wherein a shop for some widget or shmoo exists on a numerical line with potential customers distributed uniformly. These stores can compete on price and location, with the understanding that there is a calculable utility cost to a consumer traveling a given distance; it is such that a business can exceed the price of its competitors for a homogeneous good and still secure sufficient profit simply by offering a location closer to the end consumer. Hotelling thus recognizes position as a factor of monopolization: businesses at a suitable distance can act indistinguishably from standard monopolies, owing to the acquisition cost of the alternatives exceeding the monopoly price.

However, what is even more pertinent is the rule of successive development, wherein an up-and-comer seeks to break the monopoly through offering an equivalent item. In this case, Hotelling notes that the profit-seeking motive would suggest that this developer found his new establishment at the property that maximizes the number of customers closer to them than to their opposition. On the linear model, this is posited to be precisely next to the foe, offering shoppers a slightly shorter walk for the more of the same, whilst being closer to a partition of the city that will nonetheless dignify the arrangement with the name of a “business district.”

Such districts pollute our highways, with gas either being out-of-reach or concentrated in sameness, yet Hotelling’s insight does not end here. Location, as a factor, is not unique in having a calculable utility cost for consumers; so too goes the sourness of a cider, the crispiness of a chicken sandwich, or—worse yet—the very bitterness of our nation’s beer supply—Bah! Humbug! Competition inclines sellers towards minimal differentiation so as to capture the widest audience in the market. This law extends even into politics, wherein it is better known as “Median Voter Theorem”, by which a political party is encouraged to moderate its positions towards their opponents to capture greater vote share. So long as a resource is acquired by adjusting a factor to gain a greater share, one should expect systems—firms, governments, municipalities—to provide the same, concentrated accommodations.

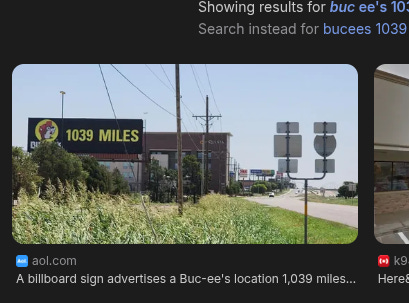

Yet, under real economic conditions, the motorist might recognize some key recent experimental developments that contradict Hotelling’s concentrated analysis. In particular as he travels through the south-easterly United States, he might spot a cryptid, buck-toothed beaver-boy adorned with a red trucker hat beneath a righteous, yellow halo of yore’, who exclaims chipmuckedily, “’Buc-ee’s’. 1039 Miles.” The absurd distance demanded to come upon what amounts to a measly “gas station”—“Is it even a gas stations?”—baffles the economic traveler. Up until being able to suppress curiosity no longer, the adventurous highwayman diverges from their linear route to see what the ‘hubbub’ is about. Only then does the mystique of raw entrepreneurship sweep aside that analytical dread common to haunting mathematicians and statisticians alike; the fear that their model may be “it”—problem and all.

The experience of a Buc-ee’s is oft described religiously and in moral terms. It is ‘the’ site of re-moralization; a demonstration that life can, indeed, simply be ‘better’. A nomadic people, long abused and resigned to crusty stalls with their empty dispensers of papered hygiene, are here at last graced by their fellows when they sit upon the porcelain throne, no longer disgusted at the accumulated grime that forces a frown upon even the grittiest. The standard fare of mass-consumable, engorging junk that litters those suffocatingingly cheap racks have been replaced with resplendent beaver nuggets and bellied brisket meals, each bearing that signature yellow smile, stickered upon the heat-preserving aluminum casing. To walk the laminated floors, perusing oddities amidst the passing crowds, is deeply amusing—unlike those cold, tired, half-dead marches back to the road, legs creaking, half-oiled with uncured fatigue. How could the wanderer not hold reverence? It is a haven.

The “Buc-ee’s” is against everything that the Hotelling factors of business should suggest not to come about. The giddy beaver is not minimal in his differentiation, but is rather maximalist; and for this praise is due—to quoth the familial review upon departure, “Why can’t everywhere in America be a Buc-ee’s?”

How has the gas empire of Arch ‘Beaver’ Aplin the 3rd, blessed be his porcelain, bucked the minimalist trend whilst other enterprises fail upwards into uniformity? To this, this writer offers three answers, The Three B’s: Brand, Bridging, and Braggadociousness. Each, in its own way, breaks Hotelling’s tidy model, allowing the carsman to drive full once more.

Hotelling’s Linear Model of the city is one-dimensional; it considers only one perfectly competitive product being sold by N different firms. However, in a real market, it is the case that many firms end up selling near-products, offering different characteristics, each providing their own utility. One can consider slight differentiations in gas, such as diesel, mid-grade, premium, or in politics, local dog-catcher, treasurers, and governors; These differences can recalculate where the maximal profit-seeking position is for a business. Even so, the power of Hotelling’s Law remains—though extended in models like Steven C. Salop’s Circular City, wherein consumers select between preferred differentiated and undifferentiated products from firms positioned around a ring.

To truly resist Hotelling’s Law and gain profit advantage through differentiation, one can consider not just the product but the business’s “Brand”; a business is not what a product makes. Even with a singular undifferentiated product, once bundled together with another, the calculations for the optimal spatial placement adjust with each additional item gravitationally pulling towards the ideal storefront—or, alternatively, policy position for securing votes.

This phenomenon of bundling can be broken down even further; one can consider a product to be made up of characteristics with each acting individually to attract consumers. As a concrete example, consider the opening of a pub serving Belgian beer—rich and high in alcohol—between a German beer hall, restrained but strong-willed, and a Czech lager house with its rich yet light selection. This venture can acquire the picky consumers, malt-lovers and heavy drinkers, from both. The point of profit maximization for this new joint would depend on the marginal customer gained from becoming closer to either competitor, but nonetheless, beer drinkers will rejoice at a new taste between sites of concentration.

Buc-ee’s “Brand” drives motorists to go the extra mile for gas. It doesn’t need to sit beside the other gas stations, as it doesn’t simply compete for gas, but rather is in the business of brisket, beverages, boutiques, beaver bites, beanies, beady beaver-bears, baggage, bling, etc.—a one-stop roadside shop.

And as a shop, Buc-ee’s wants you to shop there, so much so that it breaks a key element of the linear city model: the assumption of stable uniformity regarding transportation. People and their transportation costs are not constant and, thus, can be manipulated by profit-seeking firms, so as to generate increased revenue. For example, consider a business situated upon an island, inaccessible by anything but a boat. The business recognizes that by financing a bridge between it and the mainland, it will be able to quickly recoup its spent dollars through the newfound traffic. In doing so, the market’s cost of transportation is reduced, allowing for a more effective acquisition of desired customers.

Hotelling factors, as factors in which competitive entities acquire resources through cost-based partitions, can have their solutions jostled via this “Bridging”. By acting as an entrepreneur on a resources’ cost functions, an entity can recalculate the ideal position ahead of its competitors. Buc-ee’s does so through supporting highway redesigns, building up local communities—and thus, moving a customer base closer, wafting a sense of reach, and convincing travelers of closeness. The application of positive bridging—as opposed to negative bridging, whereby one destroys the island bridge to acquire more—allows the beaver to convince the public that refueling at its many pumps is easier than with its competitors.

This ease is made all the more apparent in consideration that beaver nuggets are not confined to a single location; the linear city model makes the assumption of a firm selecting a singular, immobile, and permanent location. The firm is not given the option of exit, nor double, nor triple, quadruple, etc. entry. A firm within the linear city might consider the acquisition of all customers by surrounding its competitors on both sides. The public would thus find it always easier to go into one of the firm’s stores over that of the competition.

In response, though, we might imagine that the competitor shuts down their location, leaving the original firm stuck with an additional location serving an identical crowd. If our firm shuts one of the duplicates down, however, the same competitor might reopen their doors, stealing back their portion of the populace. It thus becomes a game for the would-be double entrant: how may they keep greater customers in the linear city using both locations, whilst avoiding the costs associated with having an extra?

For our Texan Brand, its strategy reflects a kind of spatial maximalism that snubs being near their competitors through asymmetric excess—or “Braggadociousness”. At the time of writing, this writer notes that there’re 63 listed locations across the highways of this United States, with a third of them opening over the last five years. Each location is placed in a manner not to split customers evenly with its competitors, but to overwhelm the field through sheer scale. By going big and not going home with regard to Hotelling’s law, Buc-ee’s manages to corner the traditional gas industry by surrounding its restrainers with largess.

Through the combination of “Brand”, “Bridging”, and “Braggadociousness”, Buc-ee’s manages to thwart minimal differentiation and provide a higher degree of welfare for motorists across the country. The application of Buc-ee’s’ strategy for consumer acquisition via maximalism to other systems, like governments, offers profound problem-solving potential that can ameliorate several continuing crisis.

For consideration, this writer points to the ongoing “Housing Crisis”, wherein rents and housing costs have outpaced income growth, resulting in a politically-charged sentiment of being worse off than ages past. Whilst the outcomes for this crisis are noted to be “cost-led”, this writer points to the existence of affordable housing outside of high-income areas, albeit inaccessible without the very incomes which concentrate into overwhelmingly similar cities. This is suggestive that Hotelling’s Law of Minimal Differentiation is acting upon the resource of “Incomes”, much like how the motorist observed it operating on gas stations.

By considering the “Housing Crisis” as “Income Concentration”-led, one can gain significant insight into the ongoing systemic problem. As the number of high-to-mid incomes in an area increases, overwhelmingly they are invested by the upwardly-mobile class into “nest eggs” as a means of securing their newfound social position. When this activity is done together by thousands of others within the same geographical region, it not only drives up housing prices, but owing to density, makes it more expensive to build additional housing units. Social security demands drive residents towards “NIMBY-ism”, which further increases expense, whilst, at the same time, the cash-flushness drives demand for high-quality services requiring significant labor.

This labor is significantly challenged as their need for rentals competes against the high-to-mid incomes’ desire for housing. Developers, as profit-seekers, are slanted towards constructing family homes over affordable apartment complexes on the available land parcels. The end result lends itself to an asymmetric market with strong demand for labor that lives and accepts a lower standard of living.

The reversal of this trend, wherein similar incomes were significantly less concentrated across a couple areas, but were more broadly distributed, would provide a higher degree of welfare for civilians. This is only plausible through reversing Hotelling’s Law, as producers’ “Incomes” act as a significant Hotelling factor. Firms, when spatially considering where to hire for high-to-mid jobs, will select positions whereby they can acquire a workforce over their competitors, which, in accordance to the law, is stationed precisely next to their foes. All the while, firms themselves act as a similar factor for municipalities when they consider policy. The result is concentrated, minimally different cities with declining standards of living.

This writer thereby suggests the application of “Buc-ee’s America”, whereby “Brand”, “Bridging”, and “Braggadociousness” are applied to policy and business practice as to weaken the hold of minimal differentiation over how the American citizen lives and works. Through the development of regionally specific entrepreneurship in both practice and policy, one could alleviate spatial concentration; a Buc-ee’s American would see to the investment into local economic oddity for the sake of that places’ “Brand”. Through providing access to high-to-mid incomes off the well-beaten path, by “Bridging” policies of civil defense, frontiersmanship, and regional hurrah, one could see to the positive recalculation of being away from concentration. And by operating these policies with that “Braggadocious” American Spirit, engaging with multiple, monumental projects, each on a Manhattan-scale, our newfound exuberance will surround all laws regarding impossibilities, seeing to it that beaverly remoralization of the motorist is extended to all.

Buc-ee’s America, 1039 Miles.